This article is based on a recent paper. This paper was written by Alwin van Welie, Tim Fitters, Thijn Grillis and Rens van Balveren. The authors analyzed the WannaCry ransomware attack based on a thorough literature review. Important lessons learned were derived from this.

Introduction to WannaCry and ransomware attacks

Cybercrime is more popular than ever. The cost of cybercrime is estimated at around $8 trillion worldwide in 2023, and researchers expect this will rise to almost $24 trillion in 2027. One of the most significant cyberattacks was the WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017. From 12 May 2017 until 15 May, this attack locked around 300,000 computers in more than 150 countries. Identifying the lessons learned from WannaCry can help companies to prevent and minimize the impact of ransomware attacks in the future. To identify the lessons learned, this research first focuses on creating a timeline of WannaCry to identify what happened and analyze the impact on the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. At last, the most significant lessons that can be learned from the WannaCry ransomware attack are derived.

Cybercrime is expected to explode soon

Cybercrime is expected to explode soon. The cost of cybercrime prevention will rise from more than $8 trillion worldwide in 2023 to $23.82 trillion in 2027 (Fleck, 2022). With the emergence of more and more malware attacks, the need for awareness, prevention, and security measures/procedures has become incredibly high. According to Beaman et al. (2021), companies are not the only potential victims – institutions, governments and hospitals, among others, are primary potential victims. Tom Hoffman, 2020, for example, predicted that by 2021, a new organisation would fall victim to ransomware every 11 seconds (Hofmann, 2020). In addition, according to the National Coordinator for Terrorism and Security’s Cybersecurity Image of the Netherlands 2023 report, the digital threat remains undiminished and constantly evolving. The worsening relationship with Russia creates an increased risk (Ministry of Justice and Security, 2023).

Countries attacking each other

Countries do not shy away from using cyber-attacks on each other. According to Desouza et al. (2020), there are numerous cyber-attacks in which countries are suspected as the brains behind the attack. Governments thus use information systems to harm hostile countries or political opponents, such as the hacking of the 2016 US presidential election by Russia, the planting of malware in an Iranian nuclear power plant by the US and Israel and the WannaCry cyber-attack, which North Korea is accused of (Desouza et al., 2020.

It has not been the first time we’ve seen countries attack each other. Another recent article about cyberwarfare among nations also noted this.

Major global cyber security issues and costs

The paper by Lallie et al. (2021) shows that major global issues, such as COVID-19, cybercriminals and governments, see opportunities to carry out cyberattacks. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the risk of cyber-attacks has increased for all companies worldwide, including countries not in conflict with Russia but who are just allies of Russia’s enemy (Gartner, n.d.; Jazeera, 2023; Security Encyclopedia, n.d.).

It is now common knowledge that governments carry out cyber-attacks on countries with which they are in conflict as well as those countries’ allies, and the damage these attacks cause is unprecedented. It is also a logical weapon because, through cyberattacks, states can cause significant damage to the infrastructure or economies of an enemy state undetected and in secret. According to Almashhadani et al. (2022), the WannaCry and the NotPetya attack is estimated to have caused over $8 billion worth of damage.

WannaCry depicted: what happened and what was its impact?

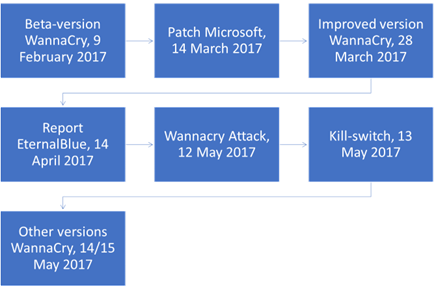

The Wanna-cry attack happened incredibly fast. In more than two days, more than 150 countries and more than 3,000,000 computers have been infected. To discover what happened and how big the impact was, a timeline with global events has been elaborated, and for every event there is looked at the impact on the NHS case.

Beta-version WannaCry, 9 February 2017

The first encounter with WannaCry was on 9 February 2017, at this date researchers from Fortinet discovered the first sample of WannaCry which they named the beta-version. This version encrypted files using the AES-128 algorithm (Akbanov et al., 2019).

Patch Microsoft, 14 March 2017

On 14 March 2017 Microsoft patched their operation system, in this patch was a Server Message Block(SMB) vulnerability, SMB is a protocol that allows for sharing data between computers and devices on a area network. This network makes it easy to access files and resources from other computers on the network. The SMB vulnerability made it possible to connect to TCP ports 139 and 445. This connection could be made by sending messages to an SMBv1 server, which resulted in the connection.

Improved version WannaCry, 28 March 2017

The second encounter with WannaCry was on 28 March 2017 again by the researchers of Fortinet, at this date they found the new version of WannaCry. This new version used hardcoded dictionaries to access server message block shared files and dropped a Tor browser download link in the cfg file (Akbanov et al., 2019).

Report EternalBlue, 14 April 2017

On 14 April 2017 a group Shadow Brokers release NSA Hacking tools, this release exists of a lot of information on vulnerabilities in software applications including EternalBlue. The EternalBlue exploit was originally manufactured by the NSA, but the NSA did not publish the vulnerability to Microsoft after they detected it. The vulnerability became public after the shadow broker got access to the NSA report and published it.

WannaCry Attack, 12 May 2017

On 12 May 2027, just after 13:00, the Digital Care Computer Emergency team of the NHS alerted the DHSC that four NHS organisations were affected by the ransomware. At 16:00, already 16 NHS trusts were impacted by the virus. At this point, the NHS brought its existing emergency, preparedness, resilience and response plan into action. This plan consisted of three parts: securing the emergency care pathway, assuring primary care was operationally stable, and the last part existed out of ongoing remediation, wider system actions and the anti-virus update (Smart, 2018).

Over the course of this Friday evening, the NHS gave a national conference call, the NHS released a cyber bullet with a technical description of the ransomware and remediation advice, and the NHS took part in an incident briefing with the Secretary State of Health. In the meantime, local organisations worked to resolve and prevent infections (Smart, 2018).

Kill-switch, 13 May 2017

On the evening of 12 May 2017, a UK malware researcher discovered a kill switch. For WannaCry, this random kill switch domain name was: “iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com”. When a computer gets infected, the algorithm checks if it can connect to the domain. If this is not the case, the worm starts with encrypting the files (Akbanov et al., 2019).

It is still uncertain why this kill switch was included in WannaCry, but it is possible that this is included so that ransomware could check if it is in a sandbox. A sandbox is a virtual machine that is not connected to the internet to execute untrusted files and check what they do. Since a sandbox is not connected to the internet, it imitates a real response. So when the ransomware gets a response, it shuts itself down so the sandbox does not detect it. But the consequence of this was that after the domain was registered, the ransomware always fought that it was in a sandbox, and the result of this was that the virus stopped spreading (Zimba et al., 2018).

After the spread of the malware had stopped, the Digital Computer Emergency team of the NHS worked together with the DHSC to inform and help local NHS organisations with restoring devices and addressing vulnerabilities. The initial focus was on securing and protecting the emergency care services. Local NHS trusts also collaborated in the form of conference calls to share knowledge, resources and information with the goal of supporting the response and resolution. On 13 May, five acute trusts were diverting patients, and a couple of trusts had trouble with diagnostic services (Smart, 2018).

The attack explained: taxonomy

The studies by Almashhadani et al. (2022), Zimba and Mulenga (2018) and Beaman et al. (2021) conclude that the hackers behind the WannaCry attack used a vulnerability in the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol of Windows to send ransomware worm, as an attack vector. The US Secret Service NSA discovered this zero-day vulnerability. They did not report this vulnerability to Windows, but they created an exploit called EternalBlue to exploit this vulnerability. Eventually, this exploit was leaked to a hacker group named Shadow Brokers, who used it to carry out the attack.

Affected companies

The target of the WannaCry attack were companies that were running on a Windows Operating system. Windows had already implemented a countermeasure through updates, but the attack was still thriving on outdated (end-of-life) systems or systems that had not implemented the updates. This shows how important it is for organisations to keep updating their systems. In addition, the question remains, however: Why did the NSA not report this exploit to Windows? This can be answered as follows. Governments are so busy waging cyber warfare that they need to catch up on the primary purpose of cybersecurity, which is to protect their systems from attacks. An opposite goal has been achieved because they have not reported this vulnerability but have tried to exploit it for their purposes. They fell victim to their own exploit.

Low threshold to pay the ransom

WannaCry’s payload was a ransom that the victims had to pay to regain access to their files. The WannaCry attack was not unique in adding ransomware to a worm to exploit a vulnerability. The threshold to pay to gain the key to decrypt all files again was very tempting. This was because the amount that had to be paid was ‘only’ 300 dollars, which was increased to 600 dollars once. After a week, the files would become ‘forever lost’. Because many small organisations were hit, they could afford to lose 300-600 dollars instead of the often thousands to millions of dollars asked to decrypt files.

How can organizations influence the impact of a future attack?

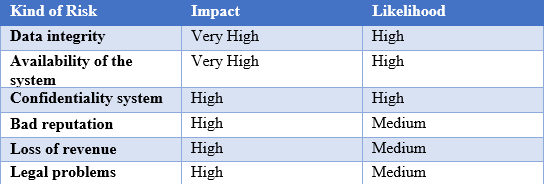

The WannaCry attack was several years ago now, but there remains a risk of another attack. There always remains a residual risk for companies, meaning they can never fully protect themselves from ransomware attacks. Some risk sentences are mapped out in the following matrix:

To minimise these risks, companies can take the following steps:

Mapping the size and complexity of the organisation and network helps understand where an attack could occur and how it could spread (Zimba & Mulenga, 2018). Increasing employee cyber awareness and training employees can also be used. Using software-defined networking (SDN) to identify and respond to threats (Akbanova et al., 2019) as well as updating the security measures regularly and backing up data regularly (Beaman et al., 2021) are major improvements.

Lessons learned: damage minimization

Quite a few lessons can be learned from the WannaCry ransomware attack. They are as follows:

- Always update your operating system as quickly as possible. A lot of patches regarding (known) vulnerabilities will be released pretty fast in general by Microsoft for Windows for example. This way, known vulnerabilities and in a lesser sense zero- day exploits won’t be as big of a threat to organisations using operating systems.

- The WannaCry-vulnerability was patched for almost two months as mentioned before, prior to the attack itself. The attack was so successful since a lot of organisations did not update their systems prior to the attack, even though Microsoft had already acknowledged and released updates to prevent any vulnerability to be exploited.

- No ‘private or closed-off’ organisation is completely risk-free. The known exploit in the Windows operating system was a SMB vulnerability. This vulnerability made it possible to connect to TCP ports 139 and 445. The connection could be made by sending messages to an SMBv1 server, which resulted in the connection.

- One of the ways to prevent such an event to happen again, is to regularly update all software of IoT devices, software and operating systems. Basically, everything that uses some form of SMB. In the case of WannaCry, this exploit became known and was fixed by Microsoft itself.

- Ransomware will continue to exist. Using a worm to exploit a known vulnerability was just one way of executing a ransomware attack.

- It is therefore recommended to regularly check the latest papers, documents and reports from organisations which specialize in ransomware prevention and the latest trends in ransomware.

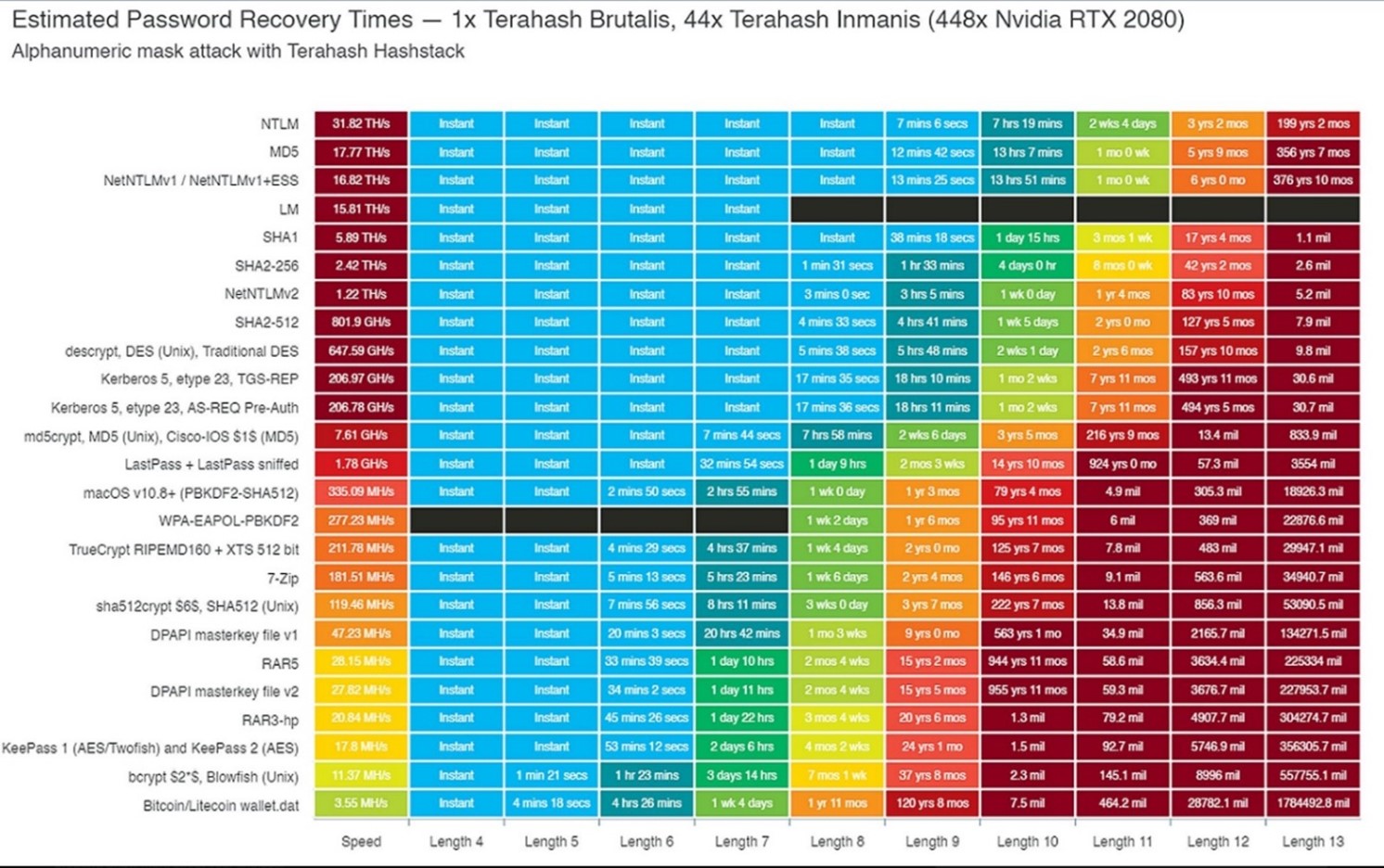

- Updating passwords regularly to (mandatory) strong passwords is a must. Since many cyber-attacks can also occur by different ways of unauthorized log-ins by third-parties, making the potential risk as low as possible regarding passwords is crucial. Setting up a good password policy for employees (and for personal usage as well) is key. At least 12-13 characters should be the minimum in the policy.

- Terahash, a corporation which specializes in password cracking, created a table which showed how long it took to crack a password using a cluster of 448x RTX2080s (Terahash, 2019) graphical cards. One of the key lessons learned from this graph is that a password should at least have a length of 12-13 characters, otherwise a Brute Force attack could in some cases almost immediately crack the password.

Conclusion

WannaCry has proved that cyber-attacks are not only common; they have impact on a worldwide-basis. Ransomware attacks have become increasingly more common throughout the years – and WannaCry was just an example. When looking at the timeline of the WannaCry attack we can recognise several phases, the first ones are the multiple evaluation of the ransomware before the attack to ensure that it is working correctly. Secondly, a kill-switch to the attack to stop the ransomware, and third a further evolution of the ransomware after the main attack has happened and was stopped. For the taxonomy of the WannaCry attack it was clear that the target were the Windows 7 users that were attacked via a ransomware worm that had a payload that demanded for between 300 and 600 dollars. This worm exploited the Service Message Block vulnerability of windows. Even though we were lucky to find an exploit in the WannaCry-code to end the attack so soon, we may be less lucky in the future in terms of risk mitigation. There are some lessons learned from WannaCry, which are the following:

- Always update operating systems and software as soon as possible. This way, ‘zero-day exploits’ will be patched in the first update after the exploit has been made known.

- Update passwords frequently and setup or improve password protocols. Passwords containing of 12/13 characters are less likely to be hacked than shorter ones. Longer passwords are better than unique passwords, because of increasing computing power which will help more successful BruteForce-attacks in the future.

- Risks will always be present, so be ready for them. Risks will always be present, no matter which preventative actions are taken. So, having a plan to execute when one actually happens is a must.

References

Akbanov, M., Vassilakis, V. G., & Logothetis, M. D. (2019). Ransomware detection and mitigation using software-defined networking: The case of WannaCry. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 76, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.03.012

Almashhadani, A. O., Carlin, D., Kaiiali, M., & Sezer, S. (2022). MFMCNS: a multi-feature and multi-classifier network-based system for ransomworm detection. Computers & Security, 121, 102860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2022.102860

Beaman, C., Barkworth, A., Akande, T. D., Hakak, S., & Khan, M. K. (2021a). Ransomware: Recent advances, analysis, challenges and future research directions. Computers & Security, 111, 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2021.102490

Beaman, C., Barkworth, A., Akande, T. D., Hakak, S., & Khan, M. K. (2021b). Ransomware: Recent advances, analysis, challenges and future research directions. Computers & Security, 111, 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2021.102490

Desouza, K. C., Ahmad, A., Naseer, H., & Sharma, M. (2020). Weaponizing information systems for political disruption: The Actor, Lever, Effects, and Response Taxonomy (ALERT). Computers & Security, 88, 101606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2019.101606

Fleck, A. (2022, December 2). Cybercrime Expected To Skyrocket in Coming Years. Statista Daily Data. https://www.statista.com/chart/28878/expected-cost-of-cybercrime-until-2027/

Hofmann, T. (2020). How organisations can ethically negotiate ransomware payments. Network Security, 2020(10), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1353-4858(20)30118-5

Jazeera, A. (2023a, March 29). Russia intensifies cyberattacks on Ukraine allies. Russia-Ukraine War News | Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/29/russia-intensifies-cyberattacks-on-ukraine-allies

Jazeera, A. (2023b, March 29). Russia intensifies cyberattacks on Ukraine allies. Russia-Ukraine War News | Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/29/russia-intensifies-cyberattacks-on-ukraine-allies

Lallie, H. S., Shepherd, L. A., Nurse, J. R. C., Erola, A., Epiphaniou, G., Maple, C., & Bellekens, X. (2021). Cyber security in the age of COVID-19: A timeline and analysis of cyber-crime and cyber-attacks during the pandemic. Computers & Security, 105, 102248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2021.102248

Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid. (2023, July 6). Cybersecuritybeeld Nederland 2023. Publicatie | Nationaal Coördinator Terrorismebestrijding En Veiligheid. https://www.nctv.nl/documenten/publicaties/2023/07/03/cybersecuritybeeld-nederland-2023

Six Russian GRU Officers Charged in Connection with Worldwide Deployment of Destructive Malware and Other Disruptive Actions in Cyberspace. (2022, July 13). https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/six-russian-gru-officers-charged-connection-worldwide-deployment-destructive-malware-and

Smart, W. (2018). Lessons learned review of the WannaCry Ransomware Cyber Attack. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/lessons-learned-review-wannacry-ransomware-cyber-attack-cio-review.pdf

Terahash. (2019, Juli 27). Ever wondered what a #hashstack @hashcat cluster of 448x RTX2080s could fo for #password #cacking? How about 31.8TH/s on NTLM, 17.7 TH/s on MD5. Estimated Password Recovery Times – 1x Terahash Brutalis, 44x Terahash Inmanis (448x Nvidia RTX 2080). Austin, Texas, Amerika. Opgeroepen op October 3, 2023, van https://twitter.com/TerahashCorp/status/1155112559206383616

What is cybersecurity? | Gartner. (n.d.). Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/en/topics/cybersecurity

What is NotPetya? 5 Fast Facts | Security Encyclopedia. (n.d.). https://www.hypr.com/security-encyclopedia/notpetya

What’s ahead for Cyber-Physical systems in critical infrastructure. (n.d.). Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/3-planning-assumptions-for-securing-cyber-physical-systems-of-critical-infrastructure

Zimba, A., & Mulenga, M. (2018). A Dive into the Deep: Demystifying WannaCry Crypto Ransomware Network Attacks Via Digital Forensics. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325678210_A_Dive_into_the_Deep_Demystifying_WannaCry_Crypto_Ransomware_Network_Attacks_Via_Digital_Forensics#fullTextFileContent